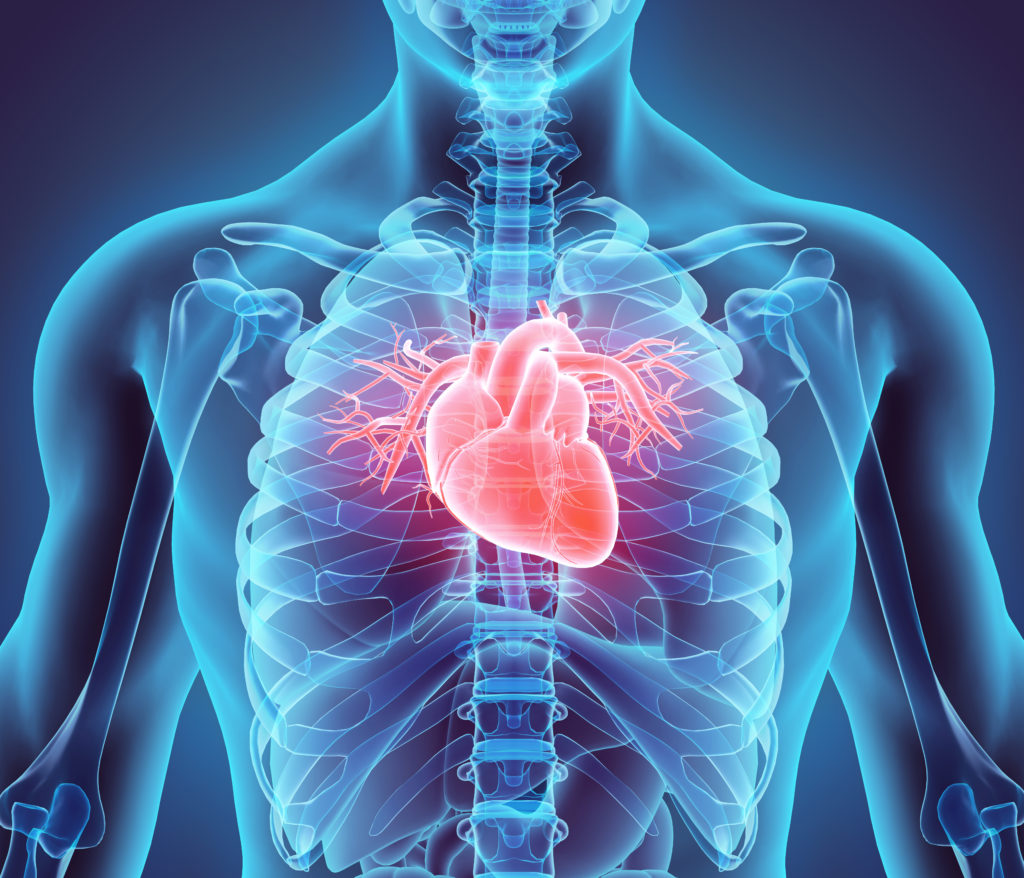

Fractional flow reserve (FFR) has been a useful tool in guiding decision-making in intermediate left main coronary artery (LMCA) stenosis, particularly in the absence of downstream disease.1 Multiple caveats have been raised about the use of FFR with significant downstream disease and the interpretation of the significance of the LMCA stenosis.2 On the other hand, very little emphasis has been placed on the importance of the FFR transducer location and the amount of myocardium subtended, presumably because, in most cases, the left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex (Cx), both supply a large amount of myocardium that would easily clarify whether blood flow is limited from a LMCA stenosis. However, this may not always be true as illustrated by this case.

Case report

A 69-year-old man was referred for angiography for Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class III angina. He previously had stents implanted in his right coronary artery, LAD and first obtuse marginal branch. A coronary angiogram showed intermediate LMCA stenosis (Figure 1). Due to severe radial artery spasm and vessel tortuosity, catheter manipulation was challenging. As such, it was elected to perform FFR of the LMCA through the diagnostic catheter. The pressure wire could only be advanced into the ramus intermedius (RI) and pressure transducer for few millimetres distal to the lesion, and intravenous adenosine (140 mcg/kg/min) was administered to achieve haemodynamic response; FFR was 0.87 (Figure 2). On the basis of the unchanged coronary anatomy, compared to a previous angiogram 3 years earlier, except for mild angiographic progression of the LMCA stenosis and the non-ischaemic FFR value, it was elected to treat the patient medically.

One month later, the patient reported improved but persistent CCS II angina. On the basis of the symptoms and angiographic severity of the left main lesion, the patient was brought back for FFR and intravascular ultrasound of the LMCA lesion through the femoral approach to overcome the technical difficulties faced in the previous procedure. FFR of the LMCA lesion was performed in all three daughter vessels (LAD, Cx and RI). Again, FFR was non-ischaemic (0.86) in the RI consistent with the previous assessment with the pressure wire greater than 10 mm distal to the lesion. However, FFR was in the ischaemic range for both the LAD and the Cx (Table 1, Figure 3). Intravascular ultrasound of LMCA showed a minimal luminal area of 5.6 mm2 (Figure 4). The patient was referred for coronary artery bypass surgery.

Discussion

FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in non-left main lesions has shown better long-term clinical outcomes compared to angiography alone in stable ischaemic heart disease.3,4 Furthermore, numerous studies support the use of FFR to assess intermediate LMCA coronary stenosis.1,5–7 However, as with any diagnostic test, the technique and limitations of its applications should be understood.

The reliability of FFR for simple LMCA lesions is rarely an issue, but interpreting the LMCA FFR in the presence of significant downstream branch lesions, such as an LAD stenosis, is a recognised challenge. LMCA and the downstream lesions act as serial lesions, and the true flow across the LMCA is potentially reduced by a severe downstream stenosis, resulting in false elevation of the LMCA FFR when measured in the unobstructed vessel.2,8 Less emphasis has been placed on the importance of the location of the FFR transducer in the absence of downstream stenosis and its relation to the amount of myocardium supplied by the daughter branch.9 For an accurate FFR, maximal hyperaemia must be achieved across the LMCA stenosis. Flow through the LMCA is the sum of the flow in all daughter branches, the magnitude of flow being proportional to the size of each artery’s viable myocardial bed.

This case points out that the size of the daughter vessel and the amount of myocardium it subtends is a factor in determining the measured FFR. In this particular case, the RI was small with a small subtended myocardium, and despite the LMCA lesion, the blood flow required during maximal hyperaemia was adequate. In small coronary arteries pressure recovery occurs within 1–2 mm distal to stenosis,10 and the fact that the transducer could only be advanced few millimetres distal to the lesion should not have affected the FFR measurement. Additionally, the fact that the FFR value on the second study was essentially the same as the first is in keeping with the accuracy of the first measurement. On the other hand, both the Cx and LAD were larger vessels with larger subtended myocardium and both showed ischaemic FFR. Thus, it is important to keep in mind that the pressure transducer needs to be in a larger daughter vessel of the LMCA when measuring FFR in order to be used appropriately for clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

FFR is well accepted as a valuable tool in clinical decision-making of intermediate left main stenosis. This case illustrates an important consideration in its use. Specifically, if the pressure transducer is in a small daughter vessel, typically a small RI or Cx, the FFR value may be in the non-ischaemic range due to the limited area of myocardium subtended by the vessel when, in fact, FFR measured in a larger vessel may show ischaemia. The case emphasises the need to measure FFR in all the daughter vessels, especially those with the largest myocardial territory.