Introduction: Cardiac arrest in relatively young patients is a difficult presentation to manage, with multiple potential causes. Establishing an accurate diagnosis is crucial and has implications on first-degree relatives. Here we present the case of a 56-year-old female with a first presentation of cardiac arrest, highlighting some of the diagnostic and treatment challenges encountered.

Case presentation: A 56-year-old lady with a past medical history of hypertension, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, high body mass index (BMI), a right hemicolectomy for bowel cancer with ongoing chemotherapy and no significant family history, presented to the hospital feeling generally unwell on the advice of the oncology team. She had recently restarted her chemotherapy (capecitabine) after a viral illness and became unwell shortly after. Whilst undergoing initial assessment, patient suffered a cardiac arrest with ventricular fibrillation in the emergency department. She was successfully resuscitated following direct cardioversion. Initial investigations were unremarkable apart from raised cardiac troponin of 600 ng/L. A 12-lead ECG demonstrated atrial fibrillation with a corrected QT interval of 343 ms. Following the neurological recovery, invasive coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries, and a cardiac MRI (CMRI) was requested to exclude myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA) and demonstrated a structurally normal heart, with evidence of non-specific diffuse myocardial fibrosis. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was inserted for secondary prevention inserted and she was referred for genetic testing for a likely diagnosis of short QT syndrome.

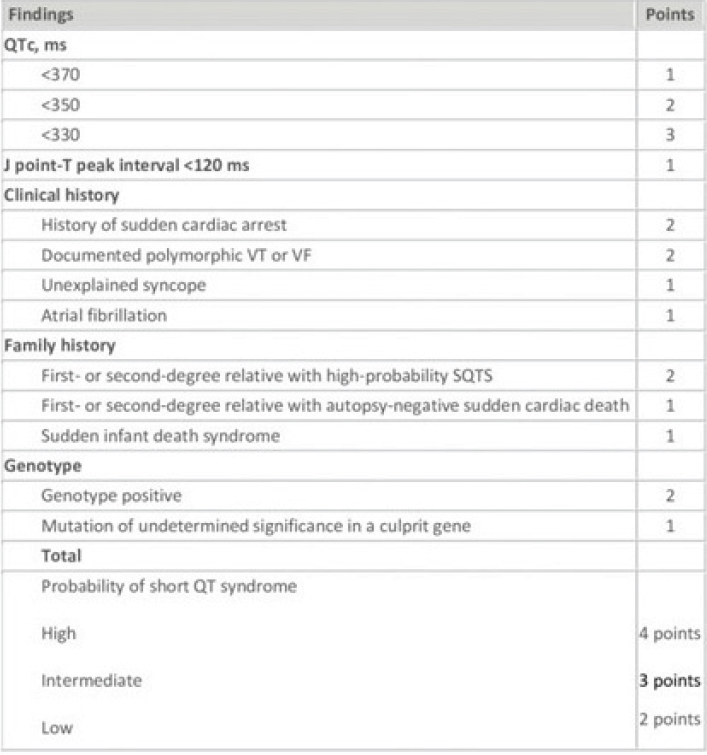

Discussion: This case is a diagnostic dilemma due to two possible causes of her cardiac arrest, both with significant consequences. The possible coronary vasospasm caused by capecitabine will have implications on her cancer treatment, along with short QT syndrome, which requires family screening. Coronary spasm secondary to capecitabine is a well-known side effect. Usually presenting with chest pain, however cardiac arrest remains a possibility. Here, the diagnosis will lead to capecitabine discontinuation with an impact on bowel cancer survival. However, the absence of CMRI changes made this an unlikely explanation. Short QT syndrome (SQTS) is a rare, hereditary channelopathy. It is associated with an increased risk to develop atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias in the absence of structural heart disease. Gain-of-function mutations of potassium and loss of function mutations of calcium channels result in an abbreviated repolarization phase during action potential and shortening of the QT interval. The clinical diagnosis is based on the scheme summarised in Table 1. ICD implantation is recommended for all survivors of sudden cardiac arrest or patients with documented spontaneous sustained VT with or without syncope. Quinidine and sotalol may be considered for asymptomatic patients with SQTS, if family history of sudden cardiac death is present. Screening of first-degree relatives should always be considered after formal diagnosis.

Conclusion: Establishing the underlying cause of cardiac arrest should be pursued vigorously, due its implications on management. SQTS is rare, but important cause of cardiac arrest and should not be neglected. Survivors of cardiac arrest secondary to SQTS should have an ICD implant and be referred for family screening. ❑

Table 1: The Short QT Syndrome Diagnostic Scoring Scheme